Sofie Kalsson

Please share a bit about yourself and your background.

I grew up on the Swedish west coast, near the sea, which continues to inspire my work. As a teenager, I developed an interest in culture and textiles, making my own clothes and drawing inspiration from the patterns, silhouettes, and color palettes of the 1960s and 70s. Initially, I considered a career in fashion as a way to work creatively with textiles.

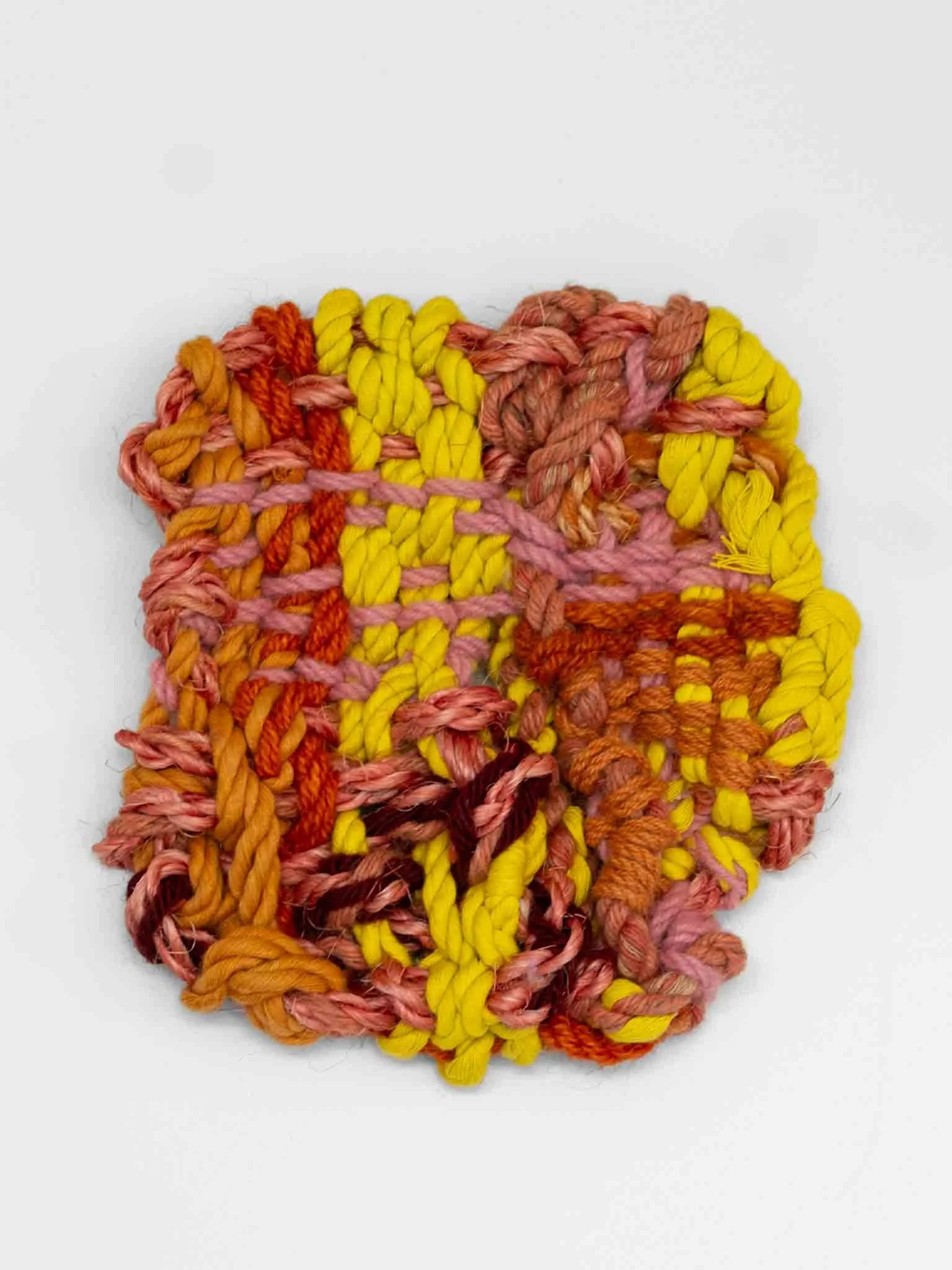

Eventually, I was introduced to textile craft and art. In 2016, I began a degree in Textile Art, completing my Master’s in 2024. Today, I work from a studio in Gothenburg, creating knotted and woven textile works. My practice draws on both my immediate surroundings and the places I visit, reflecting a broader engagement with nature and space.

What first drew you to textiles, and how did weaving, ropemaking, and macramé knotting become central to your practice?

I was first introduced to weaving while studying textile craft and design at a pre-university school in 2010. At the time, I didn’t enjoy it; I felt that the loom created a distance between my body and the material, and everything I made felt flat and disconnected. My perspective changed when I discovered the work of Veronica Nygren, a Swedish textile artist and designer known for her experimental tapestries, rich in color and diverse materials. Her work introduced me to other artists from the 1960s and 70s who also approached the loom experimentally. This inspired me to explore off-loom weaving techniques and to combine weaving, ropemaking, and knotting, allowing me to create three-dimensional forms within a cohesive body of work.

How has growing up in Halmstad and now living in Gothenburg shaped your relationship with materials, textiles, and traditions?

Growing up in Halmstad, I didn’t have access to a larger artistic community, but my family encouraged creative pursuits. Moving to Gothenburg for my studies introduced me to a supportive network of peers and local galleries, which has shaped how I engage with materials, textiles, and craft.

Travel and exposure to different cultures have also been important for my practice, providing perspectives on textile traditions and ways of working with materials. I have visited places such as Iceland, Ghana, India, and Morocco, and during my bachelor studies I spent an exchange semester in Japan. These experiences deepened my understanding of textile as a medium, particularly its historical connections to women’s work, and highlighted how communities and practices connect across borders. Inspiration for my work comes from both my immediate surroundings and these broader, cross-cultural experiences.

Your work often explores women’s historiography and domestic craft traditions. How did this interest begin, and how do you see it evolving in your artistic practice?

Textiles have historically been considered women’s work, often produced in the home and largely overlooked in traditional histories. I am interested in this invisible labor and the soft objects it creates, as they offer insight into cultural and social histories. The idea of making out of necessity has been a strong inspiration in my practice, showing how creativity can emerge from limited resources. I am particularly drawn to the accessibility of textile materials, such as how an old sheet can be reused and transformed into something new. By setting aside expectations of utility, I explore how textiles can generate new forms of artistic expression that both honour historical practices and connect with contemporary ideas. This approach continues to evolve in my work as I experiment with scale, repetition, and the interplay between material, technique, and symbolic meaning.

Could you walk us through your creative process, from choosing materials to assembling knots and threads, and share what part of it feels most alive for you?

For me, the creative process begins with the material. The qualities of a particular fibre or piece of fabric often guide the direction of a work. I frequently use leftover materials from the textile industry or items from second-hand shops, which adds both unpredictability and a sustainable dimension to my practice. A piece is usually finished when the yarn runs out, and what I initially plan does not always translate visually, so I need to remain open and adaptable. Sometimes combinations I imagined in advance do not work in practice, requiring constant adjustments. I usually work within set time frames and start with simple sketches to guide the process, but the work often takes its own path. The part that feels most alive is the direct interaction with the materials and threads, where repetition, touch, and movement shape both form and meaning.

Your practice involves a lot of deliberate, hands-on processes like weaving, ropemaking, and knotting. How does the physical act of working with your hands shape the meaning of your work and the connection you feel to the materials?

The physical act of working with my hands is central to my practice. Spending time with the materials allows me to understand their properties, strengths, and limitations, and to discover how they respond to manipulation. I usually start with simple sketches, but much of the work develops intuitively, guided by touch and movement. Whenever possible, I work standing, engaging my body fully in the process. The contrast between the raw, heavy qualities of the materials and the attention to fine details even in large-scale works is important to me. Scale becomes a tool in itself, as enlarging certain elements while keeping others small or intricate creates tension and dialogue within the piece. For me, the act of making is a combination of skill, chance, and responsiveness to the materials, allowing both form and meaning to emerge through hands-on engagement.

Where do you see the greatest potential for preserving and honoring traditional local crafts in today’s world?

In today’s individualistic world, I see great potential for preserving and honoring traditional crafts through collective work and collaboration. Working with other textile artists allows us to actively sustain and pass on textile traditions while supporting each other’s practice and making our work more visible beyond the immediate craft community. Since becoming active in the field, I’ve observed textile art gaining recognition both within the wider art scene and in people’s homes, and I want to contribute to this development. I am part of the textile collective Drift, a group of four female artists who work together to explore, share, and reinterpret textile techniques. Through our collaboration, we aim to create new opportunities for traditional practices to be experienced, understood, and appreciated in contemporary contexts.

Are there new directions or projects you are currently exploring that excite you and that you would like to share with us?

I am currently involved in several projects and have some upcoming exhibitions this and the following year. The next exhibition, called Musubi, is in Gothenburg the 17th of October, which I’m particularly excited about. It is presented as part of Gibca Extended (Gothenburg International Biennial of Contemporary Art). This exhibition showcases work developed during the Tottori–Göteborg Craft Exchange Project, where six Swedish artists, including myself, spent three weeks in Tottori, Japan, exploring local craft traditions and techniques. The works in the show reflect this dialogue between contemporary artistic practice and traditional craftsmanship, engaging with materials such as textiles, wood, metal, ceramics, and paper. In Musubi, I continue to investigate knotting and weaving as both technique and concept, responding to the knowledge and practices I encountered in Tottori and integrating them into my ongoing artistic exploration.

Where and how can people engage more with your work or learn about upcoming pieces?

On my Instagram: sofiekarlsson.textile, I post ongoing work and processes, while my website: www.sofiekarlsson.com, displays both older and newer works.

All photos by Sebastian Kok.